It was the best of times.

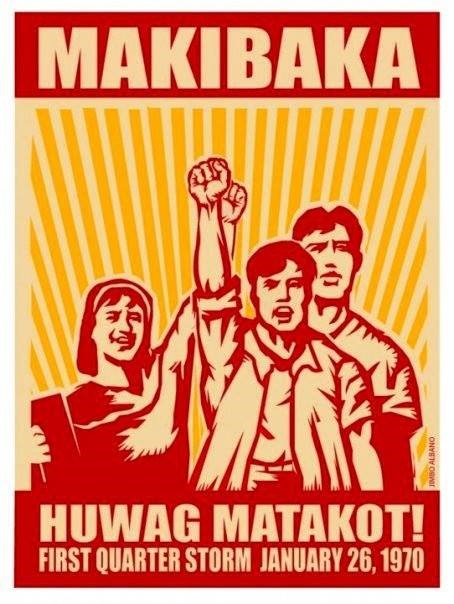

It was the worst of times. It was the time of the First Quarter Storm,

which Nelson Navarro described as “that cathartic student revolt in the

first months of the 1970 that shook the nation with its

La Gran Passion, its

intense and all-encompassing life-changing experience.”

The “Storm” was triggered

by the fraudulent presidential elections of November 1969 in which the

incumbent unleashed his 3-G formula of Goons, Guns, and Gold to secure

an unprecedented second term.

But while the public

responded to this massive fraud with fatalistic resignation, the

students were enraged. Throughout the Greater Manila area, student

councils and related organizations gathered together in preparation for

a massive protest rally in front of the Philippine Congress on its

opening session.

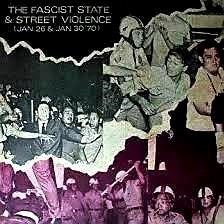

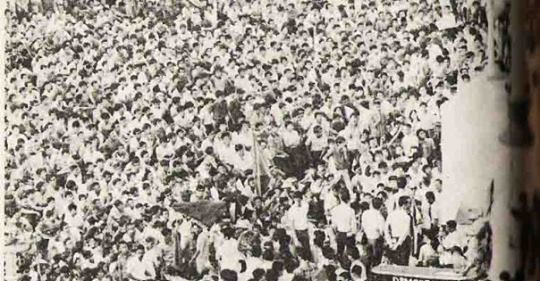

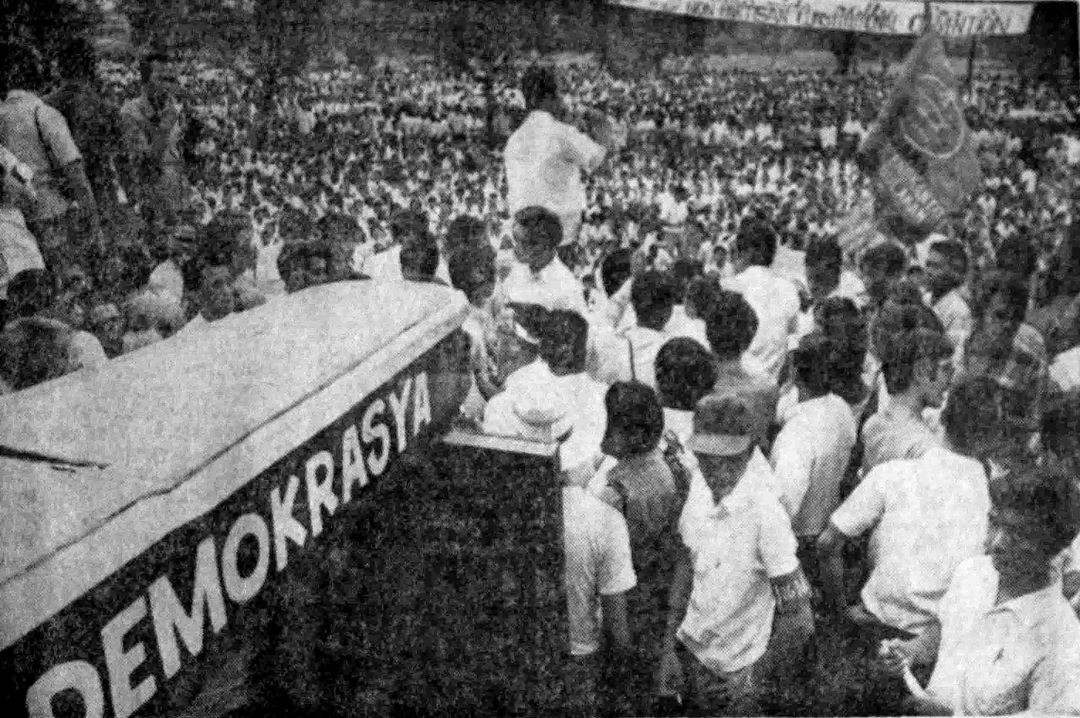

On January 26,1970, more

than 60,00 students amassed in front of Congress to listen to speeches

describing what they believed to be the true state of the nation while

Ferdinand Marco gave his own self-serving version to the self-serving

politicos inside.

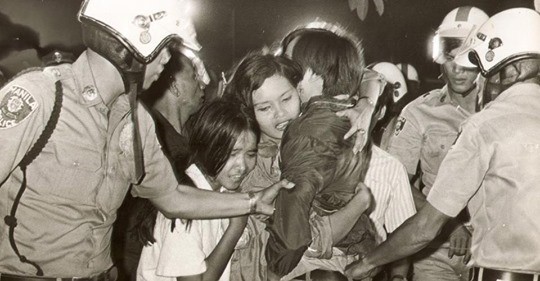

After finishing his

speech, Marcos quickly made his exit from Congress and, just as he was

about to board the presidential car, a papier mache crocodile (the

symbol of political avarice) was hurled at his car. Instantly, the

phalanx of government soldiers then charged the rank of the assembled

throng swinging their rattan truncheons and bashing the heads of the

helpless students. Hundreds were seriously injured as the whole nation

watched the tumult live on their TV screens.

In the days that followed,

indignation rallies denouncing police brutality were held in many

campuses culminating with the

January 30 March to

Malacañang. Thousands of students surrounded the fortified palace when

suddenly, the light went off and the eerie silence of darkness became

deafening.

The riot police retreated

into the night only to be replaced by battle-hardened soldiers armed

with high -powered armalites out to quell a rebellion. Before that long

dark night was over, four students were to lie dead, score paralyzed,

and hundreds maimed from gunshot wounds.

As Mario Taguiwalo

recounts its, “The death of friends. The terror of gunfire, the taste of

a truncheon taught a lot of ‘isms’ in one night. By the morning of Jan.

31,1970, a thousand chapters of student organizations had begun taking

root in school and communities nationwide.”

On the 20th anniversary of

that historic day, I found myself at Freedom Park in front of Malacañang

at the scene of that epic battle between unarmed students and fully

armed soldiers. There were simple ceremonies to mark the occasion and

small cast of notable from that period gathered together to remember.

There was Jerry Barican,

then the radical president of the UP Students council and now a

conservative lawyer and businessman. Jerry rationalized his political

transformation by quoting from Churchill:” If you’re not a radical by

the age of 18, you have no heart. If you’re still a radical by the age

of 40. You have no head.”

There, too, was Nelson

Navarro, then the articulate spokesman of the student coalition, now an

acerbic columnist and political analyst. Mario Taguiwalo was present –

once a pillar of student mass action, now Cory’s Undersecretary of

Health. Also present was Diggoy Fernandez, who was a radical student

from the elite La Salle College, now a wealthy banker and adviser to the

Philippine Aid Plan (PAP). Maan Hontiveros read the Manifesto. She was

at that time a curious student, now she is a well -known TV personality

and the owner of her own communications company.

We were reunited with John

Osmena , then a freshman congressman and a supporter of the students,

presently a distinguished senator from the booming province of Cebu. Dr.

Nemesio Prudente also attended our reunion. He was then and now

president of the Philippine College of Commerce (PCC) now renamed the

Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP). ‘Doc” has survived

several assassination attempts from rightist death squads since 1986.

Also there but feeling a

bit out of place was Gen. Rafael “Rocky” Ileto, then the Commanding

General of the Army with responsibility for the defense of the palace,

now the National Security Adviser of President Aquino. “We were on

opposite sides of the gate then.” He said, “but now we’re on the same

side.”

And then there was I, once

a fledgling nationalist eager to change the world, now a practicing

California attorney and recently reelected president of the San

Francisco Public Utilities Commission.

Not there but present in

the manifesto he had drafted and faxed from New York was Gary Olivar,

then the boy wonder of the radicals, now a vice-president of a major New

York Bank with a Harvard MBA diploma on his wall.

In his Manifesto, Gary

reflected on how “a singular dream moved a generation”

“A dream so compelling in

its inception, so irresistible in its sweep that it hurled thousands of

us against the wall of this palace – as if somehow through the sheer

weight of our passions on that endless night, we would reclaim the

palace for our own.”

Gary mirrored our

sentiments when he declared that “in the conceit of our youth.” We

believed we could “repair the broken bones of a people long despoiled

and fulfill a dream of human freedom of national sovereignty, or

equitable progress for every Filipino.”

Those present in the

simple rites were now 20 years older, and at least 20 pounds heavier,

reeking with the respectable air of the very Establishment we had once

hoped to change. Except for the general and the TV lady, the cast

exhibited prosperous tummies and shy graying hairlines. The

authoritative mien of the bourgeoisies had replaced the lean and hungry

look that was the activist trade mark. The future had arrived, tomorrow

had lapsed into today, so how had we fared?

We came together to share

a collective memory of an era gone by. One simply could not have been

part of that Storm and nit been affected by its weeping fervor and the

surge of nationalist ideals. But the stark realities of a grown family

and coping with their economic needs conspired to set aside the Utopian

dreams and like gravity bring is back down to earth.

Mario the Undersecretary

reflected about the “gem” of the First Quarter Storm this: “Every time I

am tempted to give up on people, I am reminded of the utter power of

ideals deeply held and I persevere again in seeking to convince not

compel. I recall the sense of community in the whole and the sense of

helplessness in the chaos, and I realize again that futility of solitary

happiness in the midst of widespread misery.”

“As I raise my children, I

remind them of our honorable past. Of the vast reservoir of common

sentiment that drive violators, trip cutters, lane jumpers and other

unsavory characters among us.”

Mario spoke for all of us

when he wrote about the values the experience left in him:

“The courage to stand by

one’s principles, the desire to freely express one’s dream for the

nation, the willingness to pay the price , the eagerness to depend on

one’s fellowman, the exhilaration of finding new ones.”

The First Quarter Storm,

for those who lived through it, was not just a historical event. “It has

become an attitude insists Mario,” a part of a value system that colors

one’s view of society, a powerful memory that sparks one’s hopes for a

possible Philippines. These things are important in protesting the evils

in our midst as they are invaluable in affirming the good around is.”

The most poignant part of

the ceremony was the moment of prayer offered to the memory of those who

died that fateful night and in the many years since then. Ma-an read the

responsibility never to forget. To them we owed the broadest

appreciation of their heroism – whatever their particular vision of the

future, however, they chose to fight on its behalf whenever they were

taken from us.”

At the Ceremony’s

conclusion, we embraced each other firmly and with moist eyes. “Reunions

are beautiful,” Nelson mused “because the older we get. the more we

cease seeing ourselves as friends or enemies, “he said, “we are simply

survivors sharing a common memory.”

Published 1/26/2020